Dr. Nicholas Wu is developing a way to systematically identify the targets of hundreds of thousands of antibodies and their binding ability in a single experiment.

By Justin Chapman

Dr. Nicholas Wu has mapped out his future and understands he’s in it for the long haul. At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, he has already spent 10 years trying to understand how the human immune system responds to the influenza virus.

“This is going to be a career-long project,” he said. “It will take my whole career to do this. The project that I proposed is just a proof of concept, but it can go really far, if it works, which I think it will.”

The Michelson Medical Research Foundation and the Human Immunome Project announced this week that Dr. Wu and two other early-career researchers, Dr. Rong Ma of Emory University and Dr. Camila Consiglio of the Karolinska Institutet, received the fourth annual Michelson Prizes: Next Generation grants, which award $150,000 annually to investigators 35 or younger who are advancing the study of human immunology, vaccine discovery, and immunotherapy.

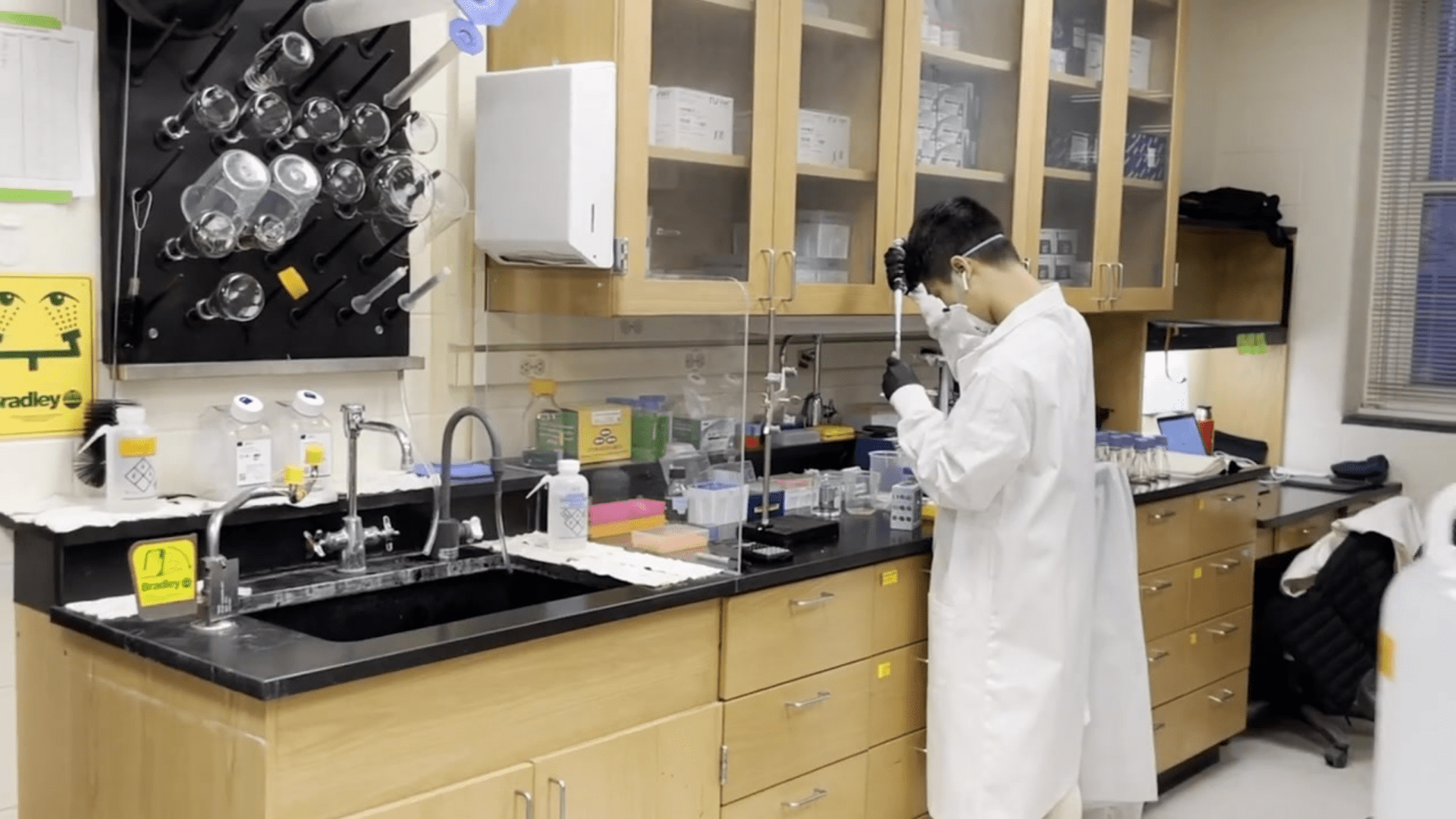

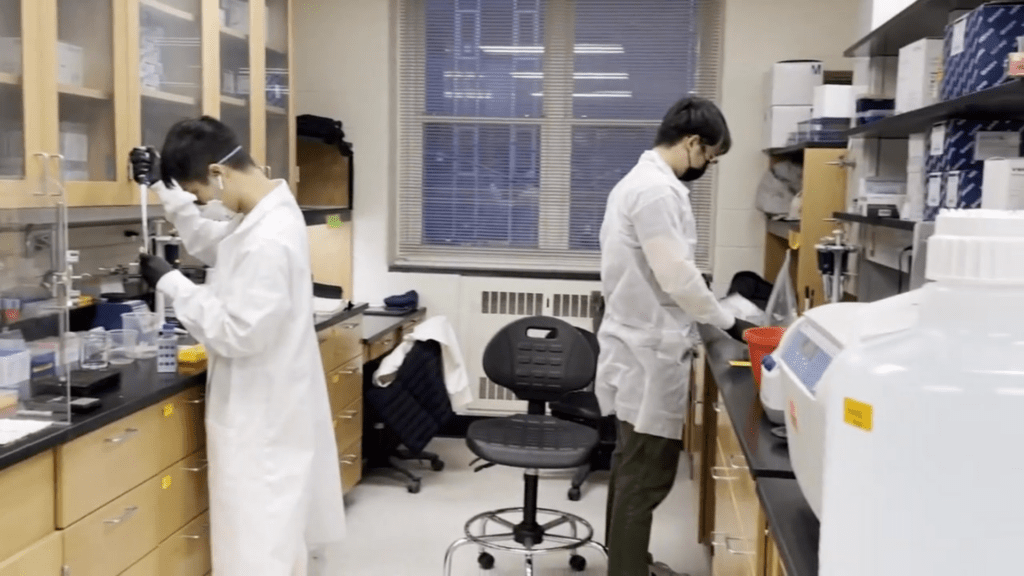

Dr. Wu studies the evolution of antigens and antibodies, which are the attackers and defenders of the immune system. He is developing a way to systematically identify the targets of hundreds of thousands of antibodies and their binding ability in a single experiment.

“A lot of what we try to do in this project is very ambitious and it’s associated with high risk, because very few attempts in the field have tried to address this issue,” he said. “The Michelson Prize will really help provide the funding, especially for the beginning of the project. A lot of funding mechanisms from the government prefer a more conservative approach and ideas. This is a very unique opportunity for me, and I’m really thankful about the award.”

Freedom to explore is a common refrain among past recipients since the Michelson Prizes were first awarded in 2018. Dr. Wu grew up in Hong Kong and moved to the United States in 2007, where he completed his bachelor’s degree in biochemistry at the University of Virginia. Then he moved to L.A. and got his Ph.D. at UCLA. For his postdoc, he moved to San Diego to study at Scripps Research before moving to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Dr. Wu’s research sits at the convergence of high-throughput biology, molecular biology, structural immunology, and bioinformatics and has the potential to significantly advance vaccine and therapeutic design.

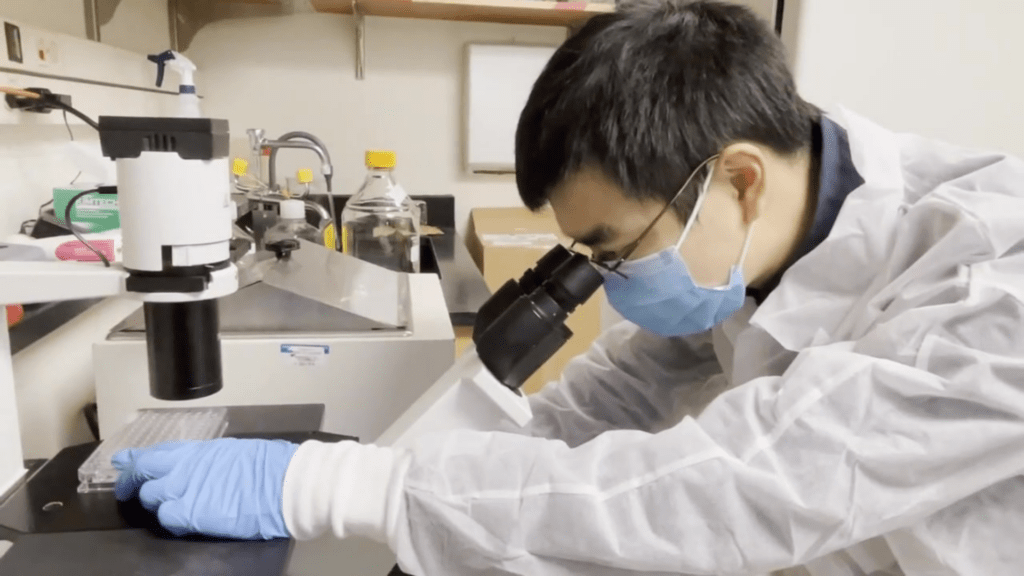

“My work has been mainly on the evolution of the virus and how our antibodies respond to virus infection,” he said. “In this particular study, what I’m interested in doing is diving really deep into understanding how our immune response recognizes the virus and how our immune system can produce all these antibodies.”

Just like there are letters encoding the DNA sequence, there is also a sequence with different amino acids encoding proteins. The sequence of the protein determines how the protein folds. The same is true for antibodies, and every antibody has a different sequence. The sequence of an antibody will determine how the antibody folds, and the folding of the antibody determines where it binds on the virus.

Dr. Wu’s research attempts to establish a sequence-based approach for epitope prediction using influenza A hemagglutinin (HA) as a proof-of-concept.

Dr. Wu plans to develop a high-throughput platform for screening antibody-antigen interactions. He will then use the platform to identify the epitopes for millions of antibodies and determine sequence features to enable epitope prediction.

“Let’s say we have a sequence of antibody that we know binds to the flu and what we are trying to do now is to predict where it binds on the flu. In the future we will try to generalize this idea to everything else,” Dr. Wu explained. “If you have a sequence of an antibody, assuming that we know exactly how the protein folds and we know all the biophysics about antibody-antigen interaction, then we can actually predict where the antibody binds and what pathogens it recognizes.

“But this is not doable at this stage because we’re missing a lot of information. Antibodies are so diverse. It’s really hard to predict where an antibody binds, because every antibody looks quite different.”

To predict where an antibody binds, Wu anticipates needing a million antibodies that bind to the same exact location on the virus in order to accurately extract features. Only then will he have enough information.

“For this project, I’m setting up this large-scale screen, a large-scale, high throughput experiment, to keep collecting this type of data,” he said. “At the same time, we can use this information to train a deep learning network. I’m taking advantage of these recent advances in computer science. We can use things like big data to train a deep learning model to learn all these features from antibodies that bind to different regions. In this case here, I’m using the flu virus as a proof of concept.” He is attempting to interpret the complexity of the human antibody repertoire.

The binding specificity and epitope of an antibody are determined by its structure, which in turn is determined by its amino acid sequence. However, accurately predicting the epitopes of antibodies from their sequences (and leveraging this for therapeutic and vaccine development) has been difficult due to a poor understanding of the relationship between antibody sequence-function.

“Rapid and accurate target identification for any given antibody will shift the paradigm of antibody discovery and characterization, as well as accelerate therapeutics and vaccine design,” he said.

Dr. Wu also offered advice for other early-career researchers who are considering applying for the Michelson Prize. The 2022 application opens April 1.

“Just try to be ambitious and don’t think about the limitations,” he said. “Don’t try to limit yourself. At least that’s what I did when I wrote the proposal.”

Read the announcement of the 2021 Michelson Prizes recipients here, and learn more here. Stay tuned for stories about the other two winners in the coming days.