Alya Michelson detailed her journey from being a female journalist in Russia’s male-dominated news industry to an immigrant and artist overcoming gender stereotypes in the United States.

By Justin Chapman

Alya Michelson wasn’t even out of journalism school when she got one of her most memorable assignments.

She was studying at Moscow State University and headed for the news agency where she was working when there was an explosion on the street in front of her on December 9, 2003. She had just witnessed, and experienced, a terrorist attack in which a Chechen women detonated a suicide bomb less than a football field away from Michelson outside the Hotel National in Moscow, killing six people and injuring 13.

“Looking back, it’s very interesting that I tried to understand the situation like a doctor would look at their patients and try to figure out what happened, instead of running for my life and thinking about how to save myself,” she said. “The first thought in my head was to pick up the phone and call my agency to report it. I was the first one in the world to report it and then I continued to develop the story in the field.”

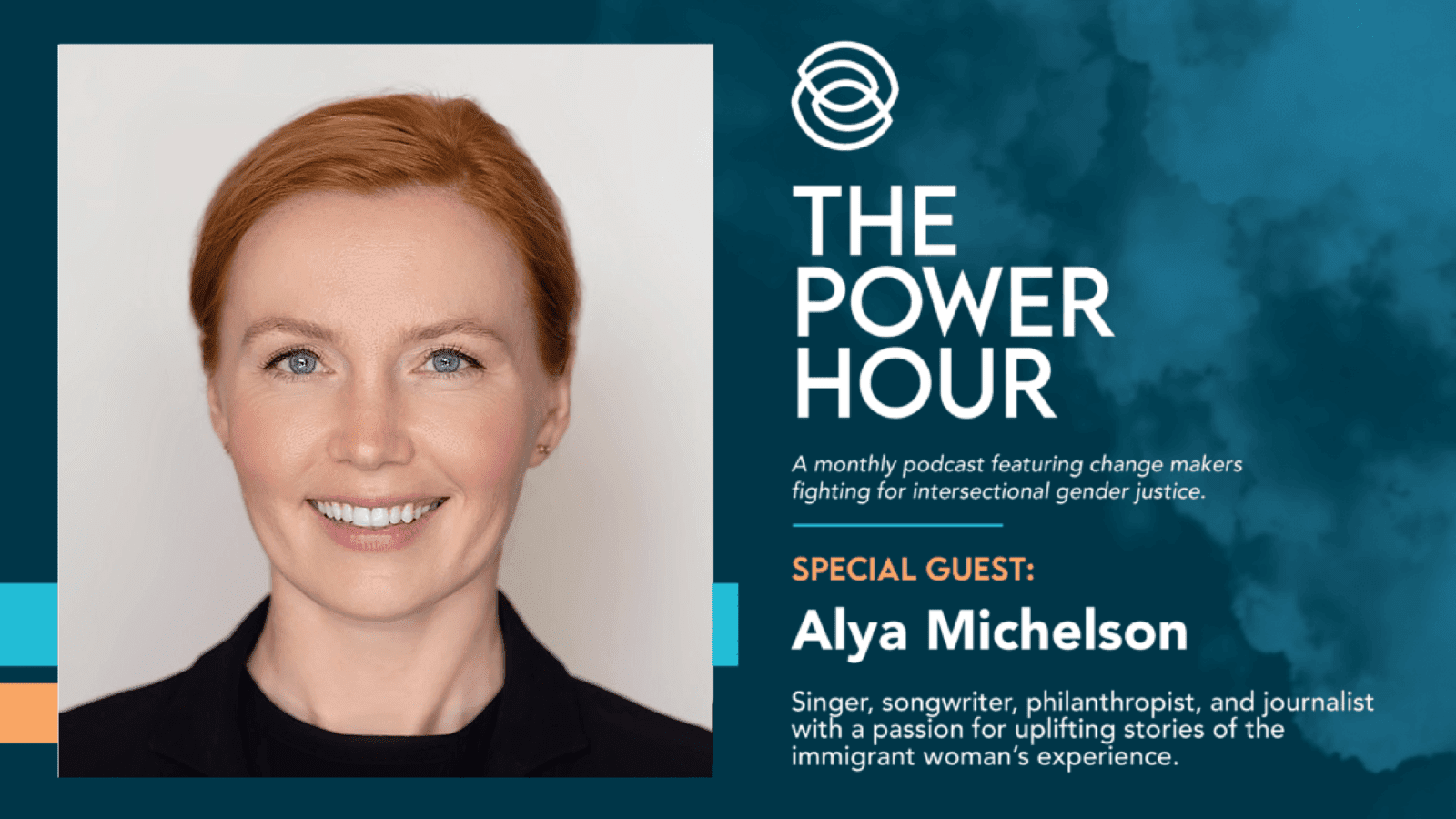

Michelson detailed her journey from being a female journalist in Russia’s male-dominated news industry covering national security to an immigrant and artist overcoming gender stereotypes in the United States during the Representation Project’s “Power Hour” podcast. Watch the full conversation here.

“Gender stereotypes are alive in journalism and any other profession. These stereotypes are very dangerous. It’s something that I’m working on trying to change.”

—Alya Michelson

The Representation Project was founded by California First Lady Jennifer Siebel Newsom to fight sexism and harmful and limiting gender stereotypes and norms through films, education, research, and activism. “The Power Hour,” which features interviews with powerful change-makers, was hosted by Caroline Heldman, executive director of the Representation Project, and Cidnee Corry of Concordia Studio.

As one of the few female reporters on the military/police/national security beat in Russia, Michelson struggled to be taken seriously by her male colleagues.

“My colleagues from other agencies and media outlets were all middle-aged men with beer bellies and ambitions who called themselves ‘legends’ and basically spent the time bullying me around,” she said. “But instead of participating in their drinking parties, I was writing stories, asking questions, and working very hard to cultivate my own sources. Newsmakers started opening up to me because they trusted me more.”

Michelson, who attended Moscow State University and reported on a number of major stories in Russia in the early 2000s, recalled the promises of freedom of press when Vladimir Putin first became president.

“I worked everywhere from news agencies to newspapers, radio, TV—both independent and state owned—and I also worked as a spokesperson, and long story short, I didn’t find freedom of press anywhere,” she said. “My decision to move from Russia permanently was partially based on my disappointment with the profession. Honest work as a journalist in Russia is incredibly challenging and the majority of my peers from the university either emigrated from the country or emigrated from the profession. I really admire those who are still trying to survive in Russia.”

Michelson and four other women were the first to break a Soviet-era tradition among MGU Journalism Department faculty that only males could be sent to study abroad, though they were still held to a higher standard in order to be accepted.

“I was told so many times that it would be better for me to focus on a family and stop feeding my ambitions,” she said. “Gender stereotypes are alive in journalism and any other profession, especially in Russia. I hope that my daughters will experience less of it here in the United States.”

But there were some things Michelson couldn’t leave behind.

“The stereotypes about Russian females are far from reality,” she said. “And it’s not just stereotypes regarding Russians, but basically any nation. These stereotypes are very dangerous. It’s something that I’m working on trying to change.”

Michelson’s experience has led to the establishment of her FirstGen Initiative, which uplifts immigrant women through storytelling that celebrates their contributions and hosts programming to facilitate their pathways to success.

“I have always believed in storytelling because it helps connect you to an issue on a personal level.”

—Alya Michelson

“I have always believed in storytelling because it helps connect you to an issue on a personal level,” she said. “The immigration issue has unfortunately been politicized and negatively colored. The media presents it as something associated with pain, death, or taking something away from the people who live here already. But it is also bravery. It’s also power. It’s also a resilience. It’s love, but nobody talks about that. I felt I could fulfill this niche as a storyteller, an artist, and a journalist, and that was how FirstGen was born.”

When she moved to the United States, Michelson also moved into a new profession. She became a singer/songwriter and her new single, “Pleasure Is Mine,” is getting noticed.

“Unlike journalism, music felt like something that couldn’t be censored,” she said. “It gave me a voice when I was shy to speak, and I was very shy of who I was. I was shy of my accent and my appearance, of my cultural heritage. I was an outsider. I was foreign and I was already pre-judged and often misunderstood because of cultural differences. And that inspired me and directed my path as a musician. These days I purposely try to use cultural allegories and archetypes to complete this story about myself, about being a Russian female, about my Slavic heritage.

“Sometimes I look back at the route I took and can’t believe it all happened.”

Watch the full conversation here. Learn more about the FirstGen Initiative here.